This post is a response to the article “The Vitamin Myth: Why We Think We Need Supplements” written by Paul Offit in 2013.

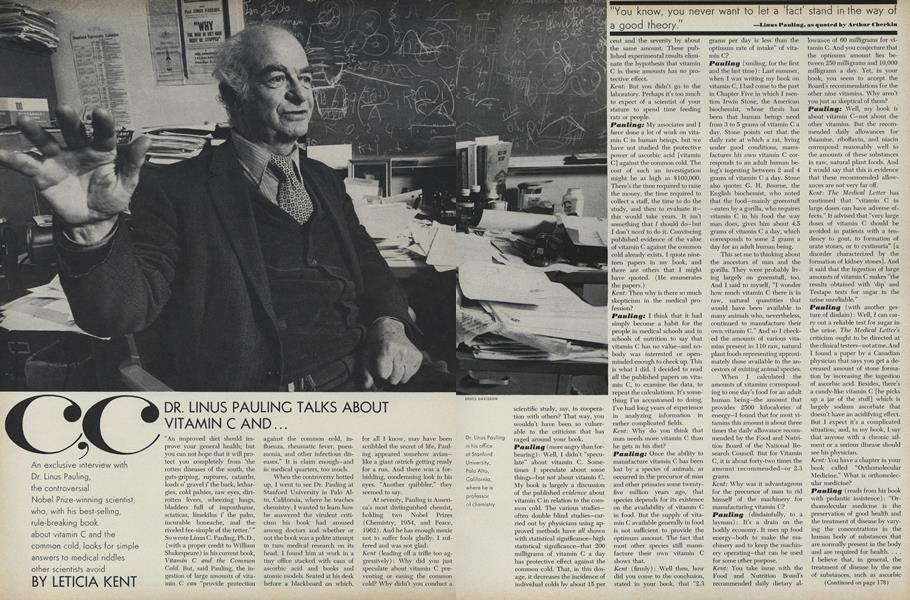

Vitamins perform a vast number of functions in the body from aiding in growth and digestion to even nerve function. The National Institute of Health estimates that more than one third of all Americans take a multivitamin daily and virtually every vitamin needed by the body can be consumed in pills or gummies. Though vitamins are supposed to be consumed in a balanced diet, supplements have gained a lot of momentum in the health industry as people believe certain vitamin supplements can benefit their wellness or cure ailments. Claims in particular about vitamin C in the past have been exaggerated by reputable scientists and exacerbated by the media.

In “The Vitamin Myth”, Paul Offit describes a phenomenon of pseudoscience spreading like wildfire around the United States after the Nobel Prize winning Linus Pauling began to make claims of curing diseases and extending life expectancy as a result of increasing vitamin C intake. Offit introduces Pauling by his many accomplishments and awards that catapulted him to his fame as “the most outstanding young chemist in the United States” (pg. 2). “In 1961, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine’s Men of the Year issue, hailed as one of the greatest scientists who had ever lived,” (pg. 3) Offit cites. But apart from his discoveries of electron sharing as a molecular bonding tool, sickle hemoglobin’s reaction with oxygen, the secondary structure of proteins, and the date of evolutionary divergence of humans from gorillas, he was also known as a worldwide peace activist. Offit lists that he “opposed the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, … opposed nuclear proliferation, publicly debated nuclear arms hawks like Edward Teller, forced the government to admit that nuclear explosions could damage human genes, convinced other Nobel Prize winners to oppose the Vietnam War” (pg. 3) and for his efforts won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1962.

Then at the age of 65 his career took a dramatic turn for the worst after Pauling touted the miraculous health benefits of outrageous amounts of vitamin C. He urged the public to take thousands of milligrams of vitamins to cure basically any issue although many studies showed that there were no benefits to excessive use of vitamin supplements. He lost his great reputation in the scientific community after his obsession proved to be more harmful than anything. After his death, the research of the early 2000’s provided ample evidence that there was actually a reported increase in mortality for at risk people who took supplements.

The accomplishments of Pauling were so numerous it was startling to read just how drastic his fall from fame was. Linus Pauling is mostly remembered for his obsession with the medical benefits of vitamins, but had he looked into the research that was presented to him he would have likely agreed with their methods and results, and his reputation today would probably had been preserved. His overconfidence was likely based on a need for this research to be significant and the personal bias caused by the placebo effect. The energy and health benefits he claimed to experience firsthand could be attributed to his overwhelming confidence that the vitamins would work.

The outrage Pauling showed at the findings of Charles Moertel, of the Mayo Clinic, proves his intense personal bias for this unfounded research. Offit recognizes Pauling’s initial rebuttle that the Mayo Clinic only “treated patients who had already received chemotherapy” (pg. 6) as the issue with their study. Yet when Moertel conducted a second study with the same results, Pauling felt it was a “personal attack on his integrity” (pg. 6) and tried to sue. This seems, to readers, like such an unnecessary overreaction to this report it makes the chemist’s mental state appear fragile and unstable.

It is so ironic that Offit notes Pauling saying there was no side effects to long term use of large quantities of vitamin C and then stating seven months later his wife died of stomach cancer (pg. 10). It should have been the ultimate event for a realization of his faults, and yet he stuck to his claims until he himself died of prostate cancer a few years later. Consistently it has been shown that vitamin C doesn’t treat cancer and doesn’t cure any of the many ailments people can get.

The National Institute of Health supports that clinical deficiencies of vitamins can disrupt cognition, but an excess of vitamins will not improve brain functioning in the normal person. The market is flooded with supplements promising to improve memory or “boost” brain function; remember vitamin supplements are only beneficial to people that have vitamin deficiencies.