I never wanted to change the world or be remembered. Growing up I thought there would always be someone better than me to try to pose solutions to global needs like fair politics, climate change, and the ever elusive “Cure for Cancer”. My parents held high expectations of me, and as report cards maintained remarkable grades over the years, my family came to expect that I would be in business, or go to law school, and make a name of myself. I never wanted to be a doctor until my sophomore year of high school. I was enthralled with my introductory psychology class because of the nervous system and the complex way that it worked to organize our bodies, thoughts, and responses. I found my passion as a sixteen year old flipping through, and trying to memorize, the pages of The Brain Facts Book after choir rehearsal.

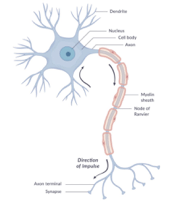

Naturally, when the school year ended and the work was over, I expressed that I wanted to continue learning at the University of Miami for my summer vacation. It was unorthodox for a rising senior to be spending the time to travel and relax instead back inside a classroom for a summer STEM program, but I knew it was where I needed to be. I studied more on the mechanism of sending a message through neurons; how dendrites would receive the message chemically, send it down the axon shaft electrically, and then trigger a release of chemicals to the next neuron. But more importantly, that summer I was first introduced to glial cells. Glial cells are supporting cells for the neurons in the nervous system. They are much more numerous than the 86 billion neurons that make up the average human, and scientists are pioneering research now that recognizes the critical importance of glial cells in regulating neuronal function.

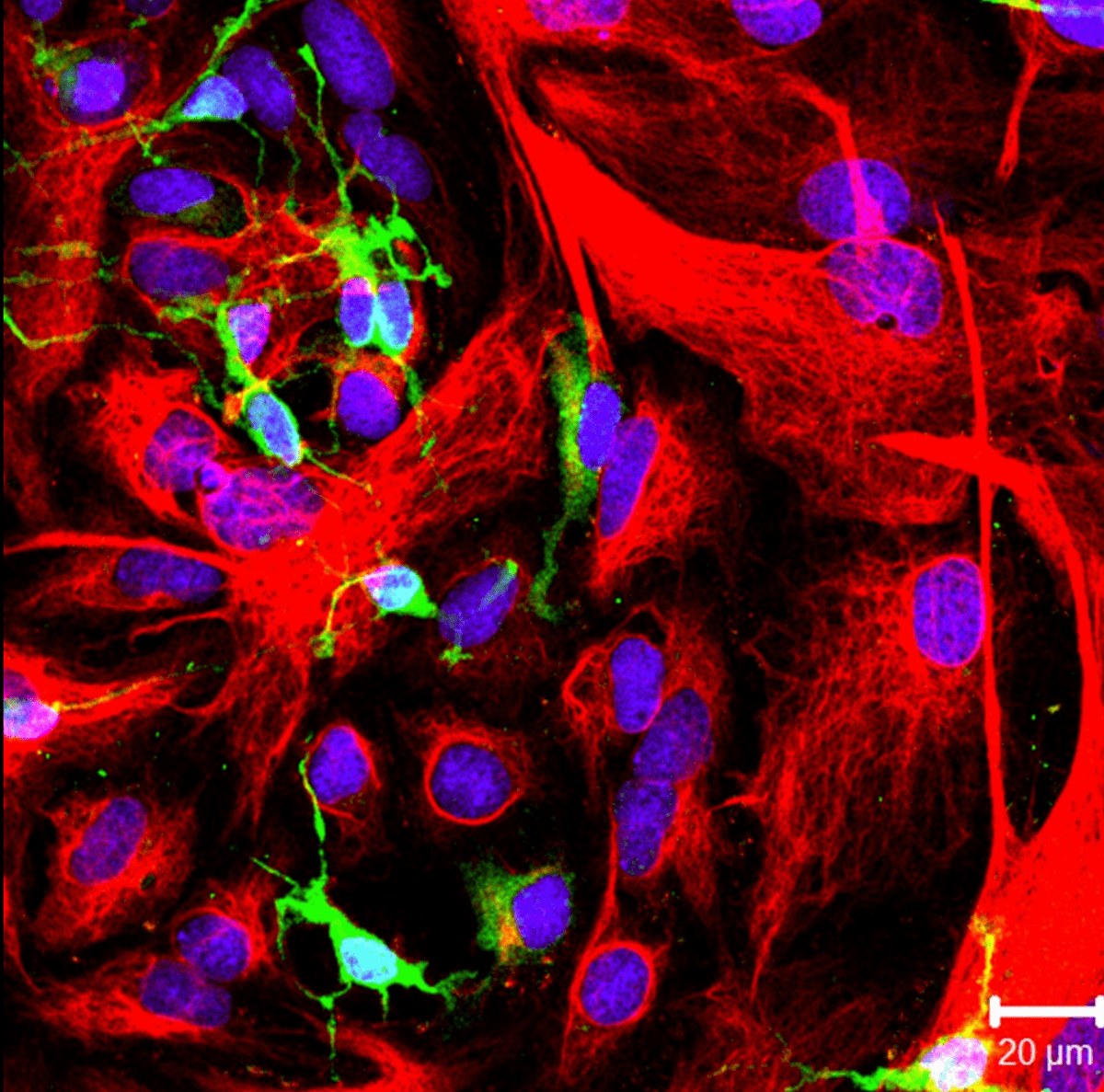

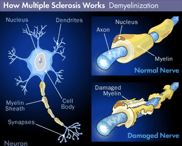

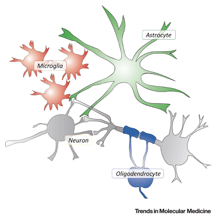

There are three main types of glial cells in the Central Nervous System: astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. Astrocytes, pictured to the right in green, are star-shaped cells that transport nutrients to the neuron, protect the brain from toxic blood vessel contact, and regulate excessive excitatory transmissions between neurons. Microglia, illustrated in red, are the fastest moving cells in the brain which allows them to completely scan the brain for danger every couple hours for issues such as debris or damage, and fight back with phagocytosis (ejection). Oligodendrocytes, depicted as blue attachments, are cells that produce a coating called myelin. This coating insulates, protects, and speeds transmission of electrical messages just like electrical wires covered with rubber preserve the voltage inside the circuit. When that myelin falls apart, it’s like a phone charger with a torn wire that must be kept in the one position that keeps charging.

When your charger breaks, it’s annoying, but it’s not the end of the world; just run to the store or even your house junk drawer to find a replacement. But things aren’t that simple with repairing brain and spinal glial cells. People with Multiple Sclerosis, a degenerative disease, have T-cells attacking their myelin, exposing their neurons to damage, and causing an eventual slowing, or stopping, of transmissions between neurons. This leads to symptoms such as numbness, spastic muscles, weakness, fatigue, vision problems, and difficulty walking because the normal signals that would be sent quickly and uninterrupted, now are tedious and choppy.

Not even one process in the brain can be conducted without the help and regulation of glial cells, yet understanding the billions of glial cells in the body and their interactions with neurons is just recently being regarded as important to unravel. I’m fascinated with the immense, slightly overwhelming amount of complexity within the nervous system, and I want to learn more.

I never wanted to change the world. I wanted to discover it.